Here they come the business men

Like a herd of cattle rumbling in

The exchange has officially begun

-Phantom Planet

I have always disliked collective, prescribed experience and have done whatever I can to avoid it. In Chicago recently, some friends and I considered joining the snake of folks queued up to take an elevator to the roof of the Sears Tower. Instead, we found a different tall building, dodged a few security guards, and took the elevator as high as we could where we looked out at an unremarkable cityscape from an empty conference room. We weren’t as high as we would have been at the top of the Sears tower, but we didn’t mind. It was fun to carve out an exploration of the Chicago canopy on our own terms. Put a different way, we were motivated by a desire for autonomy in our decision-making, as opposed to following the herd into something predigested.

Our behavior in this situation is a good demonstration of a psychological theory of motivation and personality called the Self-Determination Theory (SDT). According to SDT, people have three intrinsic motivations that guide their behavior:competence, relatedness and autonomy (Stern, 2018). The first motivation, competence, concerns our desire to do things that prove, support or develop our skills and ability to excel. For example, I am motivated to go rock climbing three times a week because I want to send a 5.12 route cleanly. Improving as a climber makes me feel good. It gives me satisfaction. Relatedness concerns our desire for social connection with others. This aspect of SDT is all about our aspiration to do something that other people will find socially desirable, which motivates us because it feels good to set a good example. Finally, autonomous motivations are encapsulated in behavior that is grounded in a desire to do something when it is presented as a choice. My friends and I had low motivation to go into the Sears Tower because it felt prescribed. However, we had a higher motivation to find a different view simply because it was a choice we made ourselves. That felt empowering.

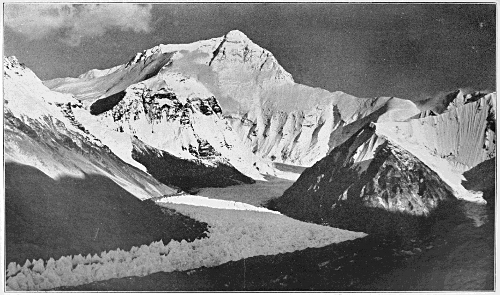

SDT is an important, and relatively unique theory within behavioral psychology, because the motivations it describes are intrinsic and not learned. That is, the behaviors it predicts are not based solely on environmental factors like norms or learned cultural motivations like values and beliefs (Deci & Ryan, 2011). Instead, they are based on widespread, innate human desires that cross cultural, historical and demographic lines. In fact, offering extrinsic rewards (i.e., offering monetary compensation for solving an interesting puzzle) has been shown to offset intrinsic SDT motivations (Deci, 1971). Essentially, George Mallory didn’t set out to summit Everest because someone offered him ten thousand dollars to do it. He did it “because it’s there.”

This presents a challenge: if you want to change a behavior that is driven by aspects of SDT, you can’t use bribes. You have to find ways to positively engage with a person’s competence, relatedness and autonomy as they already exist. If utilized successfully, refocusing these motivations toward a desired outcome can be an effective means of changing behavior in many settings, including environmental contexts.

One example of this theory being put to use is the well-known slogan of the US Forest Service’s mascot, Smokey the Bear: “only you can prevent forest fires.” This is a perfect example of framing an environmental issue in an SDT context in order to change behavior —people starting forest fires—because it frames the issue in terms that underscore a person’s autonomy. The messaging gives people a choice. It’s on on you (importantly, not “we” or “they”) to make a choice. Smoky is telling you, “friend, the destruction of this forest is in your hands, not the government, not campers in a general sense, not park rangers or cigarettes. It is up to you to make the right behavioral choice, and we trust that you will do the right thing.” Such a message engages someone’s autonomous motivations because we as people want to be validated that we have power, that we have a choice. In environmental contexts, when this direct connection to choice becomes clouded, it becomes much easier to lose motivation to work against negative outcomes. SDT tells us that when we feel in control of our decisions, we are better motivated to make the right decision. Engaging with these intrinsic motivations often boils down to offering a choice instead of instilling feelings of obligation on the part of the actor.

References

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 105.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Self-determination theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology, 1(2011), 416-433.

Stern, M. J. (2018). Social Science Theory for Environmental Sustainability: A Practical Guide. Oxford University Press.